WGLB is a multimedia news magazine. Here we discuss and promote all things GLBTQ, news, history, politics, culture, activism, family, health, entertainment, sports, religion, etc. Welcome and Join the conversation.* please sign our petitions!

Please note-

Saturday, March 5, 2011

In Memoriam: Chloe Dzubilo

Chloe Dzubilo, artist and AIDS and transgender activist, died February 18 in New York City. She was fifty years old. She was apparently overmedicated and fell in subway tracks.

Chloe studied art at the Parsons School of Design and received an associates degree in gender studies from CUNY-City College in 1999.

Originally from Connecticut, Chloe moved the East Village in 1982 and worked Studio 54 before becoming ad director for the art magazine, the East Village Eye. She wrote plays for and performed with the Blacklips Performance Cult (cofounded by Antony Hegarty) at the Pyramid Club, which had been founded by her partner Bobby Bradley. She also edited the Blacklips literary 'zine, Leif Sux. She also did some modeling.

Boehner Takes First Steps to Defend DOMA, Pelosi Strikes Back

Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) released a statement this afternoon strongly suggesting that the House will take up a court defense of the Defense of Marriage Act in the wake of the Obama administration's decision on Feb. 23 that it will no longer defend Section 3 of the 1996 law.

Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) released a statement this afternoon strongly suggesting that the House will take up a court defense of the Defense of Marriage Act in the wake of the Obama administration's decision on Feb. 23 that it will no longer defend Section 3 of the 1996 law.In the statement, Boehner said, "I will convene a meeting of the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group for the purpose of initiating action by the House to defend this law of the United States, which was enacted by a bipartisan vote in Congress and signed by President Bill Clinton.

According to Boehner's office, the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group is a five-member panel consisting of the Speaker of the House, Majority Leader, Majority Whip, Minority Leader, and Minority Whip. Under House rules, his office said in a statement, "the advisory group has the authority to instruct the non-partisan office of the House General Counsel to take legal action on behalf of the House of Representatives."

Boehner added, "It is regrettable that the Obama Administration has opened this divisive issue at a time when Americans want their leaders to focus on jobs and the challenges facing our economy. The constitutionality of this law should be determined by the courts -- not by the president unilaterally -- and this action by the House will ensure the matter is addressed in a manner consistent with our Constitution."

Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), while praising Obama's earlier decision as a "bold step forward for civil rights and equality," opposed Boehner's decision.

"Aside from standing up for a discriminatory law and failing to focus on jobs and the economy, this action places Republicans squarely on the wrong side of history and progress," Pelosi said in a statement. "In addition, this decision will burden the staff and monetary resources of the Office of the General Counsel, and given the complexity of these cases and the number of courts involved, it is likely this will cost the House hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars."

The Department of Justice, in a letter sent to Boehner on Feb. 25, alerted him to 11 cases in which DOJ believes its decision not to defend Section 3 of DOMA is implicated.

Pelosi continued, saying, "This is nothing more than a distraction from our most pressing challenges, and Speaker Boehner should follow his own advice and work with Democrats to create jobs, strengthen the middle class, and responsibly reduce the deficit.”

The Human Rights Campaign, which has urged Boehner to focus his attention elsewhere for the same reason, was quick to condemn the move.

"House Republican leadership has now shown they’re more interested in scoring cheap political points on the backs of same-sex couples than tackling real problems," HRC president Joe Solmonese said in a statement. "As families across the country continue to struggle, the House Republican leadership's prescription is to keep families they don't like from accessing needed protections."

Tony Perkins, the head of the Family Research Council, had been pushing for Boehner to act. He celebrated today's move, saying in a statement, "We commend Speaker Boehner and Majority Leader Eric Cantor for intervening to defend DOMA. This follows President Obama's decision to abdicate the requirement of his constitutional oath that he 'take care that the laws be faithfully executed.' A forceful intervention is a necessary response that will limit the dangerous precedent set by President Obama's refusal to defend DOMA."

=end=

Focus on the Family pastor speaks at Arcadia breakfast; dozens protest

ARCADIA - A pastor from a conservative Christian group that opposes gay marriage spoke about the importance of compassion and unconditional love in the family during a city sponsored breakfast Friday that drew protests from scores of residents and gay rights activists.

The Rev. H.B. London Jr., vice president of ministry outreach and pastoral ministries at Focus on the Family, spoke about family values to a crowd of at least 300 people Friday inside the Arcadia Community Center, receiving a standing ovation.

Greeting attendees filing into the 2011 Mayor's Community Breakfast were some 90 protesters from around the region who support the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. Waving American and rainbow flags, they chanted "we are families too" and "city funds are not for hate."

London, who served as pastor at First Church of the Nazarene of Pasadena from 1985-91, stressed the importance of unconditional love among family members, no matter what they may say or do.

"In spite of some of the things that (my sons) may have done or said that I disagreed with, I loved them unconditionally," London told the audience. "They were my sons. Nobody had a greater responsibility to them than I did...It seems that in this day and age, that in so many ways we've acquiesced to the point where maybe we've given over to social agencies the role of parenting and the role of family and we need to take that back."

Arcadia resident Gary Searer, a structural engineer, was among the protestors outside who claimed that the Colorado Springs-based Focus on the Family is neither accepting nor unconditional toward lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender individuals. "They do not tolerate people who are different and that's inappropriate for the city to spend money on this," Searer said.

|

| H.B. London, Jr., of Focus on the Family, and his wife Bev, right, visit with guests after he spoke during Arcadia's 2011 Mayor's Community Breakfast Friday, at Arcadia Community Center. |

"I just believe this is democracy and if they disagree with my appearance here, they have every right to disagree with it as long as they are peaceful and respectful. Whatever they say or do is their conscience," London said after the event. "They are speaking their conscience."

While he believes strongly in marriage between one man and one woman, London said he accepts those with differences of opinion.

"I respect their right to do what they do and to believe what they believe," he said.

London also argued that Focus on the Family "has not been intolerant" but rather advocates what it calls "a biblically based position" on such issues.

"I think he's really courageous every day because he's transgender," Aizumi said of her son. "He goes out and tries to live his life the way he was meant to be. So for me to come today is to support all the LGBT people and especially my son. I want to be courageous, too."

Ten police officers and a SWAT vehicle were stationed outside the community center to ensure public safety at the event. Police said there were no problems.

Focus on the Family, originally founded in Arcadia in 1977 by Dr. James Dobson, believes that marriage should be between one man and one woman and advocates "reparative therapy" as one way to change unwanted same-sex attraction.

Besides an unknown amount of staff time, the city's contribution to put on the event is estimated to cost between $5,000 and $5,500, said Linda Garcia, the city's special projects manager.

David Steinmeier, a long-time Arcadia resident, said London's talk about family was something everyone could relate to.

"I felt his presentation was very well-balanced and a unifying presence," said Steinmeier. "He didn't single out any one particular group."

Mexico City records 700 homosexual weddings in first year of law allowing same-sex marriage

The government said Friday that 73 foreigners were among those married, and the rest were Mexican citizens. It says nine of those who got married were between the ages of 71 and 90 years old.

The federal government challenged the law but Mexico's Supreme Court upheld it in an August ruling.

=end=

Sydney's Mardi Gras hits on same-sex marriage

"We will be sending the message tonight that our love is no different and it shouldn't be treated differently by the law," participant Alex Greenwich told AFP.

Greenwich, who is the national convenor of Australian Marriage Equality, said about 2,000 of the close to 8,500 mostly flamboyantly dressed marchers taking part would be in groups highlighting the issue of gay marriage.

"There are civil unions in Australia in different states but the key thing is ... that we (reject) we should have a second-class form of relationship recognition. The issue is about equality," he said.

Labor Prime Minister Julia Gillard has stated that she believes marriage should be between a man and a woman, but has encouraged debate on the topic amid what gay marriage supporters say is widening public support for change.

"I do believe that in our society, with our heritage, with our traditions, with our history, that marriage has a special place and special definition, so I've been very clear about that," Gillard has said.

The streets of central Sydney are expected to be awash with colour and music for the 34th parade -- one of best known gay pride events in the world -- which begins at sunset and winds along the Oxford Street shopping and nightclub area.

But participants say that despite progress on gay rights since the first Sydney Mardi Gras in 1978, when male homosexuality was still illegal in the state, the fight for equality goes on.

Peter Murphy, who took part in Sydney's first Mardi Gras -- which ended in a riot and more than 50 arrests after police forcefully intervened -- said the event had always had a sense of fun despite its serious message.

"It was meant to be dancing, it was meant to be music, costumes and frivolity and a friendly message," he said.

"The original concept is still there today, it's just unbelievable how huge it is. Mardi Gras has kept its character all the way in long in fact."

=end=

Lion King animator says only a matter of time before ‘gay families’ appear in Disney films

|

| Andreas Deja says Disney may be open to featuring gay families in their films in the future |

Andreas Deja, award-winning veteran animator for Disney, has suggested the company would be open to featuring both openly gay characters and gay families in future projects.

Mr Deja, who is gay and worked on The Lion King, Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast said to News.com.Au:

“Is there ever going to be a family that has two dads or two mums? Time will tell. I think once they [Disney chiefs] find the right kind of story with that kind of concept, they will do it. It has to be the right kind of story and you have to find that first.”

Despite Disney’s conservative reputation, Disney World and Disneyland host annual Gay Day parades and last year the studio appointed Hollywood’s first openly gay studio chief, Rich Ross.

Polish-born Mr Deja also pointed out to the website that various Disney characters come from unconventional family set-ups, referring to Cinderella’s step-family, the orphaned Bambi or Aladdin growing up on the streets.

Though he added: “We are going to stay with family audiences and basically continue to do what Walt Disney tried to do.”

Pixar Studios, a subsidiary of Disney, last year featured LGBT members of their animation teams in a series of “It Gets Better” videos, which seek to offer hope to LGBT teenagers.

=end=

Michelangelo Signorile Interviews Nikolai Alekseev

|

| Nikolai Alekseev under arrest |

The controversy continues. Sirius/XM’s Michelangelo Signorile interviewed Russian gay rights activist Nikolai Alekseev, who spoke at New York’s LGBT Center last night and continues on his US tour – though coming to California is still up in the air.

Cynthia Laird of the Bay Area Reporter hopes he does.

Here’s the note Michelangelo posted on his blog The Gist:

Nikolai Alekseev, founder of Moscow Pride and man who, with other LGBT activists, has faced brutal repression and police beatings year after year as Moscow Pride was banned, is in the U.S. on a speaking tour. He spoke at the LGBT Center in New York last night and at Columbia University the night before, and now heads on to Dallas.UPDATE: Here are excerpts:

But his trip has been marred by controversy and his West Coast dates canceled over remarks on his blog that some charged were antisemitic. Alekseev says it was mistranslation from his blog, which was was in Russian. He sat down with me in studio to talk about the controversy and his work in Russia battling entrenched, state-sanctioned homophobia and fighting for LGBT rights. The full interview is [here].

Nikolai Alekseev: “Well, it’s clear what I meant by that (blog post in question). I mean, maybe it was misintepreted the way some people wanted to use it against me but obviously I didn’t plan to generalize and say that all the Jews are responsible for the decisions of the Israeli prime minister or the Israeli government. So, obviously, I was overreacting to what the prime minister of Israel said concerning the people’s revolution in Egypt. … I absolutely don’t share the generalization of this (blog) post or the way it was presented because I am a true believer in equality for everyone. … So, to quote me in this respect an anti-semite, it’s like it has no grounding at all.”

Nikolai Alekseev: “They (California organizers) never asked me (about this). Absolutely not. I was not invited to any conference call that was organized concerning my meetings in California. … Robin Tyler did not contact me on this. I didn’t hear anything from her.”

=end=

Friday, March 4, 2011

Defense of Marriage Act: That's Gay

infoMania airs on Thursdays at 11/10c on Current TV.

=end=

To thine own self...

Scarlet Letter |

| I was very far away. My real life had gone underground and could not be seen by anybody. The person at the surface that everybody saw was no longer me. --Philip Ó Ceallaigh |

I became a teacher in 1977, when I was a graduate student in mathematics at the University of Oregon. I spent five years there earning my PhD before moving on to the University of Wisconsin at Milwaukee for three years, during which time both my parents died. That sort of put the kibosh on me getting enough done to earn tenure there…and my mentor (E. H. Feller) died as well…so I moved on to the University of Central Arkansas, where I taught for 16 years.

Defense of Marriage Act will be defended by House-appointed lawyer, John Boehner says

Los Angeles Times

"It is regrettable that the Obama administration has opened this divisive issue at a time when Americans want their leaders to focus on jobs and the challenges facing our economy," Boehner said. "The constitutionality of this law should be determined by the courts — not by the president unilaterally — and this action by the House will ensure the matter is addressed in a manner consistent with our Constitution."

(Continue reading)

Surrey and England Wicket-Keeper-Batsman Steven Davies On Coming Out

=end=

Royal Air Force - It gets better...today

=end=

Navy seeks to discharge sailor found asleep in bed with another male sailor

By Craig Whitlock

Washington Post Staff Writer

Friday, March 4, 2011; 12:17 PM

To hear Navy Petty Officer Stephen C. Jones tell it, what happened in his bedroom one night last month was purely innocuous: Another male sailor came by to watch "The Vampire Diaries," and they both dozed off in the same bed. "That is the honest, entire story," Jones said.

Navy officials, however, have a different view of his bedroom behavior at the Naval Nuclear Power Training Command, near Charleston, S.C. Even though there is no evidence the 21-year-old sailor committed any hanky-panky or that his friend was not permitted to visit, Jones has been charged with dereliction of duty. The Navy is seeking to discharge him, a move that he is contesting.

"The subterfuge is, they believe this kid is a homosexual, but they have no proof of it," said Gary Myers, Jones's civilian attorney. "So what they've done here is to trump this thing up as a crime. This is not a crime."

In December, President Obama signed legislation that will eventually allow gays and lesbians to serve openly in the ranks for the first time. But the law will not take effect until 60 days after Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates and other officials formally certify to Congress that the military is ready to fully integrate gays and lesbians.

In the meantime, the Pentagon has effectively frozen many pending investigations into whether individual service members are gay. A Defense Department spokeswoman said Pentagon officials have not approved the discharge of anyone for violating "don't ask, don't tell" since at least October.

Baylor University denies charter to gay student group

Allison Ignacio - KWTX

WACO (March 3, 2011)-- More than 60 gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans-gender students and several of their straight allies, met Thursday night at Baylor

Their GLBT group, the Sexual Identity Forum, was denied a charter by Baylor University Wednesday.

Baylor senior Samantha

"Being a gay student at Baylor over the past four years I've felt neglected, not necessarily abused by the university but intentionally neglected," Jones said.

In January 2011, SIF applied to be chartered as an official Baylor organization. The Student Activities Charter Review Committee, which is made up of three staff members and two students, denied to recommend SIF's charter application to the Vice President for Student Life, who makes the official decision to charter an organization or not.

SIF revised their application but was denied a second time Wednesday.

Baylor University spokesperson Lori Fogleman said that the review committee was very forthcoming from the beginning of the process.

Arora to vote for marriage, says voters should decide

March 4, 2011

BALTIMORE SUN

Del. Sam Arora, who in recent days said he would vote for gay marriage in committee but wouldn't commit to doing so if it moves along toward final passage, has announced his decision to vote yes on the floor.

Arora, a new Montgomery County Democrat, announced his plans on his Web site.

"As the vote drew nearer, I wrestled with this issue in a way I never had before, which led me to realize that I had some concerns about the bill," he said. "While I personally believe that Maryland should extend civil rights to same-sex couples through civil unions, I have come to the conclusion that this issue has such impact on the people of Maryland that they should have a direct say."

Fear in Philadelphia That Abusive Priests Are Still Active

By KATHARINE Q. SEELYE

Published: March 4, 2011

PHILADELPHIA — Three weeks after a scathing grand jury report accused the Philadelphia Archdiocese of providing safe haven for as many as 37 priests who have been credibly accused of sexual abuse or inappropriate behavior toward minors, most of those priests remain active in the ministry.

The possibility that even one predatory priest, not to mention three dozen, might still be serving in parishes — “on duty in the archdiocese today, with open access to new young prey,” as the grand jury put it — has unnerved many Roman Catholics here and sent the church reeling in the latest and one of the most damning episodes in the American church since it became engulfed in the sexual abuse scandal nearly a decade ago.

The extent of the scandal here, including a cover-up that the grand jury said stretched over many years, is so great that Philadelphia is “Boston reborn,” said David J. O’Brien, who teaches Catholic history at the University of Dayton, referring to the archdiocese where widespread sexual abuse exploded in public in 2002.

Harvard welcomes back ROTC. Navy Secretary Mabus joins President Faust to sign agreement

|

| "NROTC's return to Harvard is good for the University, good for the military, and good for the country," said Navy Secretary Ray Mabus. "Together, we have made a decision to enrich the experience open to Harvard's undergraduates, make the military better, and our nation stronger. Because with exposure comes understanding, and through understanding comes strength." |

Harvard President Drew Faust and Navy Secretary Ray Mabus will sign an agreement that will re-establish the Reserve Officers Training Corps’ (ROTC) formal presence on campus for the first time in nearly 40 years.

“Our renewed relationship affirms the vital role that the members of our Armed Forces play in serving the nation and securing our freedoms, while also affirming inclusion and opportunity as powerful American ideals,” Faust said. “It broadens the pathways for students to participate in an honorable and admirable calling and in so doing advances our commitment to both learning and service.”

Under the agreement, Harvard will resume full and formal recognition of Naval ROTC on the effective date of the repeal of the law that disqualified openly gay men and lesbians from military service, anticipated to come in the summer of 2011.

“NROTC’s return to Harvard is good for the University, good for the military, and good for the country,” said Mabus. “Together, we have made a decision to enrich the experience open to Harvard’s undergraduates, make the military better, and our nation stronger. Because with exposure comes understanding, and through understanding comes strength.”

As a part of the agreement, Harvard will appoint a director of Naval ROTC at Harvard and will resume direct financial responsibility for the costs of its students’ participation in the program. The University also will provide Naval ROTC with office space and with access to classrooms and athletic fields for participating students. Harvard Navy and Marine Corps-option midshipmen will continue to participate in Naval ROTC through the highly regarded consortium unit hosted nearby at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), consistent with the Department of the Navy’s determination that maintaining the consortium is best for the efficiency and effectiveness of the “Old Ironsides Battalion.”

“Harvard has a long and proud tradition of service to the nation,” said Robert D. Reischauer ’63, senior fellow of the Harvard Corporation. “Today’s agreement extends that tradition in ways that will strengthen the important bond between educational opportunity and devotion to the common good.”

Harvard also has begun pursuing discussions about renewing formal ties with ROTC programs associated with other branches of the Armed Forces.

In addition to signing the agreement with the Navy, Faust announced the intended formation of an ROTC implementation committee, to be chaired by Kevin Kit Parker, Thomas D. Cabot Associate Professor in Applied Science in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, as well as an Army major who has served three tours in Afghanistan.

The committee, whose work is expected to span not only issues concerning Naval ROTC but eventually other service branches as well, will explore ways to enhance the experience of Harvard ROTC students consistent with the broad framework outlined in the new agreement.

Harvard has a long affiliation with the military. It was one of the six original partner institutions of Naval ROTC in 1926. While ROTC has not had a formal presence on campus since the height of the Vietnam War, Harvard students have continued to participate in ROTC through the consortium based at MIT. Currently, there are 20 Harvard students participating in ROTC, including 10 in Naval ROTC.

The agreement will be signed at historic Loeb House. During World War II, the Harvard president’s house at 17 Quincy St., now known as Loeb House, was turned over by President James Bryant Conant to the Navy for its V-12 training program, which supplemented the force of commissioned officers in the service. During that period, the house was operated with the same rigor as a naval vessel, with a 24-hour watch and with sailors scrubbing the oak floors and polishing the “brightwork” of the mirrors located throughout the facility.

=end=

Advances being made for LGBT medical students

By Michelle Brandt -

The most recent issue of the AAMC Reporter has an interesting article on the treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) medical students, physicians and patients. Included is a discussion of the historical challenges facing gay medical students - such as “underprepared faculty and staff, negative comments in and out of the classroom, and limited LGBT content in the curriculum" - and steps that schools are taking to aid these students and respond to any incidents:...Some medical schools have changed their reporting systems to make them safer. Drexel allows a student to anonymously submit a complaint and be quickly transferred, if necessary, to a new clinical training site. Offending clinicians can receive sensitivity training and education or, in extreme cases, be banned from working with students. Stanford provides students with the option to delay faculty notification, in case they feel more comfortable waiting until after evaluations are complete. ...The most heartening part of the article? The fact that experts say things are better now than they were just five or ten years ago. Commented Jonathan Appelbaum, MD, director of internal medicine education at Florida State University College of Medicine: “Many medical students don’t even see it as much of an issue because a diverse learning environment seems only natural to them.”

Medical schools also are working to better support LGBT students. At UCSF, an “out list” publicly lists openly LGBT students and faculty to help facilitate collegiality and networking. Open LGBT faculty members “send the message that they can advance academically and rise to high-ranking positions at an academic institution,” [Samuel Parrish, MD, associate dean for student affairs and admissions at Drexel University College of Medicine] said.

Chinese news website sparks fierce debate over gay marriage

A debate between one of China’s leading pro-gay advocates and the editor of an influential national newspaper has erupted on the one of the country’s most popular and comprehensive news websites.

As reported by SameSame, a popular Australian LGBT website, Professor Li Yinhe, a long-standing advocate of same-sex marriage, was asked to discuss the issue on the website NetEase.

One outcome of the discussion was an opinion piece by Li Tie, editor of southern China’s influential The Times Weekly. While the article reportedly acknowledges the right of gay men and lesbians to love and live together, Li Tie’s statements soon veered off in an entirely different direction, saying that treading carefully on the issue was “not an act of discrimination” because “conditions usually apply when protecting minorities’ rights.”

He continued: “The impacts of same-sex marriage include the ‘domino effect’ that it may bring upon the marriage system.

“Once same-sex marriage is legalised, it may lead to the debates on legalising ‘multi-partner marriage’ and ‘human-animal marriage’.

“If the law recognizes same-sex marriage, what about the ‘rights’ to adultery, incest or pedophilia? Does this bring a challenge to the bottom line of civilization?”

The article brought forth comments from both pro- and anti-gay readers. Some were downright hostile, including one which stated: “Gays should be buried alive so that their gay disease won’t infect more people.”

Another reader took the author to task, saying: “Do your homework well before you start to write an article like this as people will see how ignorant you are. And don’t bring up those ‘human-animal’, ‘three-people marriage’ or stories of incest again, as the attempt to represent a far vaster group with some extreme cases is clearly an act of discrimination.”

China only decriminalised homosexuality in 1997 and it remained classified as a mental illness until 2001.

=end=

Poland to speed ahead of Australia on same-sex marriage equality?

There are signs that Poland, which currently has a ban on same-sex marriage and a poor recent track record on LGBT rights, may finally be on the first step to marriage equality by providing gay men and lesbians with the documentation required to marry overseas.

Poland’s Minister for Equality, Elzbieta Radziszewska, has announced she is seeking to allow authorities to provide same-sex couples with the means they need to marry abroad.

In Australia however, the ban on issuing such documentation remains, despite a positive recommendation from the Senate as far back as 2009.

Speaking to the Australian newspaper Star Observer, the national convener for Australian Marriage Equality (AME) Alex Greenwich said the ban was “mean spirited” and that pro-marriage equality advocates would be fighting it in the courts.

“Despite a positive recommendation from the Senate inquiry, no action has been taken and the situation continues to grow worse as more countries have allowed same-sex couples to marry in the meantime,” Mr Greenwich said.

He also spoke of his disappointment over prime minister Julia Gillard’s failure to address the issue: “This is something that Julia Gillard could give the GLBT community while debate is postponed to the ALP national conference. If she wants to take action she can overturn the current policy on issuing documents and follow that Senate inquiry recommendation.”

The Star Observer also reported that a spokesman for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) told them that Australia’s Marriage Act was the real barrier to providing documentation for same-sex couples.

“It is not DFAT policy, but Australian law, which only permits the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade or an Australian Embassy overseas to issue a Certificate of No Impediment to Marriage if the proposed marriage is to be recognised as valid under Australian law,” a spokesman told the paper.

“The Commonwealth Marriage Act 1961 defines marriage as being between a man and a woman. Under the Marriage Act, a same-sex union solemnised in a foreign country is not recognised as a marriage.”

Ms Gillard has herself previously stated her belief that marriage should be between a man and a woman. Earlier this week, she played down rumours that rebel backbench Labour MPs were keen to support a Green Party bill that would give the Federal Parliament powers to override territory laws, meaning gay marriages could potentially take place in the Australian territories.

=end=

Some transgender women turn to underground cosmetic procedures

Even though she was not transgender, Claudia Aderotimi’s tragic death last month in Philadelphia underscores the dangers associated with underground cosmetic surgery. |

By Joseph Erbentraut -

Ever since the news emerged last month that a 20-year-old woman who received a silicone injection to her buttocks in a Philadelphia hotel room died, the issue of so-called underground cosmetic procedures has re-emerged into the forefront of mainstream media.

Missing in the coverage of Claudia Aderotimi’s tragic death, however, were transgender people. She was not trans herself, but many gender-variant women pursue similar treatments due to the perception or reality that they lack other options to help create a body on the outside that matches how they feel-or want to look-on the inside.

Michael Silverman, executive director of the Transgender Legal Defense and Education Fund, described these illegal procedures as "incredibly dangerous." Silverman, who also leads the Transgender Health Initiative of New York, added they often have an irreversible, long-term impact on a person’s body that can even prove fatal.

"Dangerous is an understatement," he told EDGE. "This is often industrial-grade silicone going directly into somebody’s body. Veins can be pierced, which can lead to death if the silicone travels around the body and lodges in the lungs."

Silverman and other activists, however, understand why many trans people opt to undergo these risky procedures, even while they are well aware of the dangers. A survey the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force and the National Center for Transgender Equality commissioned found trans Americans continue to suffer a disproportionate rate of discrimination in the health care system. Half of respondents said they had to educate their health care providers about trans-specific health issues. And 19 percent said doctors and other medical providers had refused to treat them altogether.

An unwelcoming and uninformed health care industry is just the tip of the iceberg of the obstacles trans Americans face when they access (or try to access) the health care system. Facing higher unemployment rates, many trans people lack health insurance. And even when employed, the vast majority of private policies do not cover hormone therapy, sex-reassignment surgery and other trans-specific procedures. Medicaid and other publicly-funded plans also do not cover them.

"We hear about this very frequently and we’re going to continue to hear about it frequently as long as the conditions we see for trans people accessing health care don’t change," said Silverman. "There is tremendous discrimination faced by trans people who feel alienated from the health care system, so as long as the main structures in the system tell trans people you’re not welcome here, they’re going to find what they need and want elsewhere."

Silicone providers should not be "chastised simply as criminals"

Elizabeth Rivera-Valentine; a community organizer with the Boston-based TransCEND, acknowledged silicone injections and other "underground" procedures are risky for trans people. She emphasized such avenues for treatment are not a new phenomenon within many communities. Her organization, which is an HIV/AIDS prevention and health care project affiliated with AIDS Action Committee, neither endorses nor condemns these procedures.

She emphasized silicone providers should not all be chastised simply as criminals who exploit a serious need some trans women who cannot afford other means to achieve a similar end have. Rivera-Valentine encourages those who may want to undergo these procedures to do their homework and thoroughly research potential providers.

"Silicone pumping has become a means of quick body feminization for a more reasonable price," she said. "If you’re going to a good silicone pumper, a lot of them really do their research and go out of their way to ensure they’re doing everything as correctly as possible."

Rivera-Valentine added, however, she often encourages other trans women to be more patient with their bodies and themselves as they transition. This patience may seem somewhat counter-intuitive to the fact those who achieve a more "feminine" appearance more quickly will not only lead to higher self-esteem, but also avoid harassment and discrimination down the road. Rivera-Valentine stressed "passing" is often central to attaining economic opportunities that are otherwise few and far between.

"I advise girls to take the time they need and do things in moderation," she said. "There are girls who are very quick to want to feminize their body and to not take into consideration the risk they’re placing themselves in."

More trans acceptance would decrease demand for underground procedures

Regardless of how one feels about silicone injections and other procedures happening outside of accredited medical supervision, it is clear their popularity points to a much broader societal shift that would need to occur in order for their demand to dissipate. Mara Keisling, NCTE’s executive director, said as visibility and acceptance of trans Americans continues to grow, the need for some to access these types of procedures will begin to decline.

Judging by controversial and decidedly transphobic depictions on media that range from Saturday Night Live skits, Super Bowl advertisements and Craig Ferguson’s late-night talk show, progress remains somewhat elusive on that front. And the lack of trans-specific laws at the local, state and federal level only exacerbates the problem.

"Families accepting and protecting and loving their children would keep people from this, an economy that allows fairer access to health care would prevent it, government policies that allow us to change ID documentation better would help stop this," said Keisling. "Like anything else, the way to stop a public health problem is always more complex than it appears to be, and it’s never as easy as telling people not to do it."

Silverman also pointed to broader concerns ahead for those who would like to see fewer transpeople accessing dangerous underground procedures. The key piece that’s missing: Affordable alternatives that safely affirm a trans person’s full identity.

"People need alternatives," added Silverman. "Until there’s political will on the part of public health authorities to achieve that, we’re going to continue to see situations where trans people are dying to get the health care we need."

Republicans: The Big Lie

By David Mixner -

Republicans have taken the road of the "The Big Lie." The theory is that if you lie with no shame and no boundaries people will hear it as fact. Any refutation of such a lie is usually heard by no one. Create deceitful storylines that either play with the truth through omission or distortion and you will have people living in fear. Increasingly, Republicans have been practicing their tainted stories with an expertise that is frightening.

Former Arkansas governor and preacher Mike Huckabee is the frontrunner to obtain the Republican nomination for President of the United States in 2012. He is not a man lacking in intellectual capacity. During a media interview this week, he embraced the big lie and appears to have gotten away with it. The preacher candidate, who clearly knows better, talked about how Obama grew up in Kenya and had more British and African values than American. There is just one problem. While Obama's father hailed from Kenya, the President never lived there and certainly didn't grow up there. The next day after the lie had time to fester in people's minds, Huckabee's spokesperson quietly announced he had misspoken. Really? How many people do you believe heard the first story and are chatting about Obama's Kenya values and never heard the retraction? Huckabee knew exactly the consequences of his lie or he is just plain stupid.

In Wisconsin, the businessman Governor Scott was caught in his big lie by a prank call. He has promised his plan to bust unions was not anti-union but essential to balance the budget. Of course in the prank call he bragged about busting unions and looked forward to spending time at the estate of a right wing billionaire Koch brothers. What was the Republican response to this episode? Well, of course, they submitted legislation to ban prank calls! Oh, the outrage!

In New Orleans a bitter ugly anti-LGBT minister whose words of hate have made our struggle for freedom so much more difficult was caught masturbating in his van at a children's playground. Isn't that what pedophiles do? His reaction was not about his double standard but an indignant proclamation that he just happened to be at the playground and the masturbation was in the privacy of his van! Some family values he is practicing on a daily basis.

This new breed of right-wing Republican dramatically takes the party of Lincoln away from traditional conservatism to a party of angry demagogues. They are more interested in bullying the LGBT community, busting unions and kowtowing to corporations than creating jobs and improving our schools. God help us.

for more from David visit Live from Hell's Kitchen.

=end=

Keeping up with LGBT health: Why it matters to your patients

|

| Diane Bruessow. RPA-C |

Ideally, patient registration should allow SGM patients to ensure their legal rights in visitation, advance directives, billing, preferred name, and so forth. The clinical interaction requires history taking that is culturally competent and knowledgeable in SGM health. Patient satisfaction evaluations should capture the experiences of SGM patients, and health outcomes should be tracked.

Some SGM patients seek care in specialized environments at lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) community health centers (http://bit.ly/fV5e9Z). Others turn to resources like the Gay & Lesbian Medical Association's provider directory (http://bit.ly/gS84FO). These options aren't accessible everywhere, however, and PAs are already encountering SGM patients—even when we don't know it. According to census data, same-sex households exist in 99.3% of US counties.1 Similar data on gender identity aren't available but are increasingly being collected in health surveys.

Just 10 years ago, the Healthy People (HP) initiative identified 29 specific objectives for which sexual orientation appeared in the data templates while, with the exception of the HIV/AIDS Surveillance System of the CDC, data identifying people by sexual orientation were not collected by any national survey or system. Gender identity and transgender health were notably omitted from HP2010.2,3 However, HP2020 contains objectives pertinent to LGBT health throughout many topic areas, and LGBT health is one of 13 new topic areas. According to the National Coalition for LGBT Health, HP2020 is remarkable for its emphasis on identifying, measuring, tracking, and reducing health disparities through a determinants-of-health approach (http://bit.ly/i3lSGf). The shortage of health care providers who are knowledgeable and culturally competent in LGBT health is of particular relevance to PAs. HP2020 recognizes this as a social determinant affecting the health of LGBT patients.

PAs can reduce the need for specialized environments by becoming knowledgeable and culturally competent in SGM health. I've seen many excellent LGBT health resources; and I suspect it's not a lack of information driving the shortage of knowledgeable and culturally competent health care providers. But I am confident that a growing body of data makes it increasingly easy for PAs to become appropriately informed. In addition to HP2020, there are other resources worth highlighting. My favorite textbook for primary care providers is The Fenway Guide to LGBT Health published by the American College of Physicians (http://bit.ly/hJIwmV). For an in-depth assessment of LGBT health data, the Institute of Medicine will be publishing a consensus report on LGBT Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities later this month (http://bit.ly/6idzM0).

National LGBT Health Awareness Week (which occurs annually in March) helps to bridge the gap between the growing body of data, clinicians, and our LGBT patients (www.lgbthealth.net). On the most basic level, we are reminded not to assume that all of our patients are heterosexual and cisgendered, and we are encouraged to improve our interpersonal and communication skills, one of the core PA competencies, by learning how and when to talk with our patients about sexuality and gender. A successful LGBT health awareness campaign will encourage LGBT patients to seek increased access to knowledgeable and culturally competent care. Will you be ready?

Whether your role is clinical, research, or administrative, take a moment to ask yourself, do you know who your SGM patients are? And do you know when and why it matters?

PAs can reduce the shortage of health care providers who are knowledgeable and culturally competent in SGM health and should avoid making any assumptions about patients' sexual orientation and gender identity. SGM patients need to receive the four critical opportunities for data collection in patient registration, clinical interaction, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes. Their health depends on it. JAAPA

Diane Bruessow practices primary care in Middle Village, Queens, in New York City. She is a member of the JAAPA editorial board.

REFERENCES

1. Smith D, Gates GJ. Gay and Lesbian Families in the United States: Same-Sex Unmarried Partner Households. Washington, DC: Human Rights Campaign; 2001.

2. Drescher J. Queer diagnoses: parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):427-460.

3. GLMA and LGBT health experts. Healthy People 2010 Companion Document for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Health. San Francisco, CA: Gay & Lesbian Medical Association; 2001.

Elizabeth Hurley Will Play Wonder Woman's Nemesis—and There's a Lesbian Twist

By Jennifer Arrow -

Who's bad? Elizabeth Hurley, that's who!

The beautiful Brit has been cast in Warner Bros.' Wonder Woman pilot as what Hurley called "the evil villain" on her Twitter. But exactly which character is that in the Wonder Woman pantheon, what's the last remaining hitch in this deal, and what's the homoerotic twist to the character?

Here's what we can tell you:

The original casting call for Wonder Woman made it pretty clear who that Veronica Cale will be the "evil villain." The breakdown describes the character thusly, "Female, open ethnicity, late 30s to early 40s. Beautiful, highly-educated, highly accomplished, she runs one of the biggest pharmaceutical companies in the country...but she's afflicted with the serious deep-seated Wonder Woman envy. Whatever she is, or will be in life...she'll never be her. And it causes her innards to rot. She loves men, but likes women. There might be an unstated chemistry between her and Wonder Woman, at least on her side."

So, we're getting Elizabeth Hurley and Adrianne Palicki together in a quasi-erotic rivalry? Sounds yummy, and it sounds exactly like the formula that made Tom Welling's Clark and Michael Rosenbaum's Lex Luthor such a formidable pairing in the early days of the WB's Smallville.

The casting is not 100 percent official, as there's still the little matter of an international work visa, but other than that, all systems should be go on this much-talked-about pilot.

=end=

Homophobia reportedly widespread in UK African communities

According to Mambo, the African healthier lifestyle magazine published by Terrence Higgins Trust, hostile attitudes towards gay men and lesbians within UK African communities is on the rise.

The current edition of the magazine reveals the experiences of gay men and lesbians in UK African communities, where people can experience lifelong victimisation, abuse and discrimination based on misguided beliefs about homosexuality.

Discriminating against gay, lesbian or trans people is a crime in the UK, but despite this, non-heterosexual Africans often suffer serious abuse, verbal and physical assault within their own community. Some are even disowned by their family. As a result of such hostile attitudes, very few gay Africans have the courage to be open about their sexuality.

In a press release from THT, Joseph Ochieng, editor of Mambo, said: “Being forced to hide your sexuality can have serious health and social consequences, not just for the individual, but also for the wider African community.

“People who are subjected to abuse and ridicule can feel isolated and find it hard to cope emotionally, losing self-confidence or the ability to forge meaningful relationships. These people are vulnerable to sexual exploitation as well as sexually transmitted infections, including HIV.”

In the current edition of the magazine, award-winning journalist Sorious Samora describes his shock at the levels of prejudice he found towards gay people during his visit to east and central Africa to film his documentary, Africa’s Last Taboo, for Channel 4’s Dispatches programme. He says that homophobia is actually being encouraged by religious leaders, the very people who should be promoting tolerance and understanding.

Joseph Ochieng said: “Thankfully in the UK we don’t have the same draconian legislation against homosexuality that some countries on the African continent do, but with homophobia on the rise here, UK Africans need to realise that being gay is not immoral and that homosexuality is not something you either learn or acquire.Tackling homophobia is everybody’s responsibility. It’s crucial that no one is made to suffer discrimination and abuse on the grounds of sexuality.”

=end=

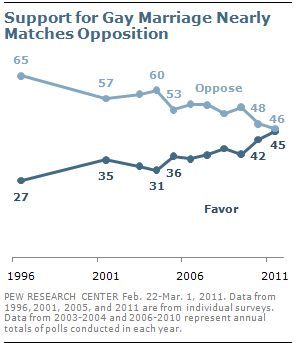

Pew Poll: Support For Gay Marriage Growing

The Pew Research Center poll found 45 percent of adults now favor allowing gay marriage and 46 percent oppose it. Forty-five percent is the highest support Pew has found for allowing same-sex marriage since they began polling on the issue in 1996. As recently as April of 2009, Pew found only 35 percent of adults supported allowing gay marriage. Other surveys Pew conducted in 2008 and 2009 generally showed support for gay marriage in the 38-40 percent range.

Pew's report notes that support for marriage is divided geographically. Majorities in the Northeast and West support marriage rights, but only 40% in the Midwest and 34% in the South favor allowing it.

- CBS News asked a three-way question in August 2010, and found that 40% support allowing same-sex marriage, 30% support civil unions, and 25% do not support any legal recognition of gay marriage. Support for allowing gay marriage was up from 30% in 2008 and 22% since they began asking the question in 2004.

- An AP-National Constitution Center poll found that 52% of adults supported same-sex marriage, up from 46% in 2009. In addition, the poll found that 58% think couples of the same sex should be entitled to the same government benefits as opposite-sex couples.

- Fox News asked a three-way question in August of 2010 and found that 37 percent of registered voters supported legal marriage, 29 percent supported some other form of legal partnership, and 28 percent favored no legal recognition. Support for marriage was up from 33 percent in 2009 and from 20 percent since Fox began asking the question in 2004.

- A CNN poll in August 2010 found that 49 percent of adults thought gays and lesbians have a constitutional right to get married legally, up from 45 percent in 2009. In addition, 52 percent said they thought gays and lesbians should have that right under the Constitution.

- A Gallup poll in May of 2010 found that 44 percent said gay marriage should be legally recognized, up from 40 percent in 2008 and 2009, though one Gallup poll in 2007 found 46 percent of adults supported that measure.

=end=

Sam Arora's disgraceful wavering on marriage equality in Maryland

Around 9:00 a.m. Thursday, Maryland House Del. Sam Arora (D-Montgomery County) -- who raised a ton of cash from the gay community and progressives based on his stance on marriage equality and who is a co-sponsor of the same-sex marriage bill now about to come up for a vote -- tweeted, "Hearing from constituents, friends. Please keep sending your thoughts (sam.arora@house.state.md.us). Thinking & praying hard." And he's been catching hell on his Facebook page ever since.

According to the Baltimore Sun, Arora has said he will vote for the marriage equality bill in the judiciary committee, but has yet to commit to voting for the measure when it hits the floor, possibly next week. "This bill deserves an up-or-down vote, so I'm voting to send it to the floor," he told the Sun. That sudden reluctance to say he will vote for a bill he co-sponsored has friends mystified and former supporters fuming, at best, calling him a liar and demanding their donations back, at worst.

Even Arora's friends from Democratic Party politics and Hillary Clinton's presidential campaign are mystified. Democratic strategist Karen Finney called his apparent change of heart "[v]ery disappointing" in a post on Arora's Facebook page. And Neera Tanden, policy director for Clinton's campaign and then the domestic policy adviser on the Obama-Biden campaign, is among those who wants her contribution refunded.

I am profoundly disappointed that supporting marriage equality is even a question for Sam. This isn't the Sam I knew and worked with, or supported in his campaign. I am asking him to return my contribution to his campaign.I should point out that Arora received the endorsement of The Washington Post last October.

One clue to how he might vote was just noticed by the folks at AMERICAblog Gay. A Tweet from Arora on Jan. 25 championing his co-sponsorship of the Religious Freedom and Civil Marriage Protection Act was deleted from his Twitter feed. Arora hasn't responded to my request to talk yet. If he does, I would ask him about that deleted Tweet. I would also want him to confirm reports by AMERICAblog Gay that he has already decided against voting for the marriage equality bill due to pressure from his church and because he doesn't want to "redefine marriage."

The outrage directed at Arora is understandable. As is the sense of betrayal. He raised money from gays and lesbians based on his support for marriage equality. He secured the endorsements of Progressive Maryland and of Equality Maryland because of it. In fact, get a load of what he wrote as an addendum to his questionnaire for Equality Maryland.

I am a former law clerk to Attorney General Doug Gansler. I publicly supported his decision to recognize out-of-state marriage licenses for same-sex couples and immediately put out a release praising his findings. For me, it's simply a matter of equal rights under the law.Gay Marylanders want the respect, dignity and responsibility that comes with marriage. And Arora was elected to his first term in the House of Delegates, in part, because of his promise to get it done. Politicians break promises all the time. But this is different. If Arora fails to vote for the marriage equality bill he campaigned for and co-sponsored when it comes to the floor next week not only would it be disgraceful, he would be a disgrace.

=end=

Thursday, March 3, 2011

Global LGBT Equality: Going All Out

=end=

Lambda Legal eNewsletter

|

| March 2011: TRIPLE VICTORY |

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Make a donation and support Lambda Legal’s groundbreaking impact litigation, public education and advocacy work. | ||

| =end= |